Who were the United Socialists: The Black anarchist squatters you’ve never heard of

On March 26, 1907, a White police officer named John Cofield visited a home on the north side of Muskogee, Oklahoma — the largest town in what was then called

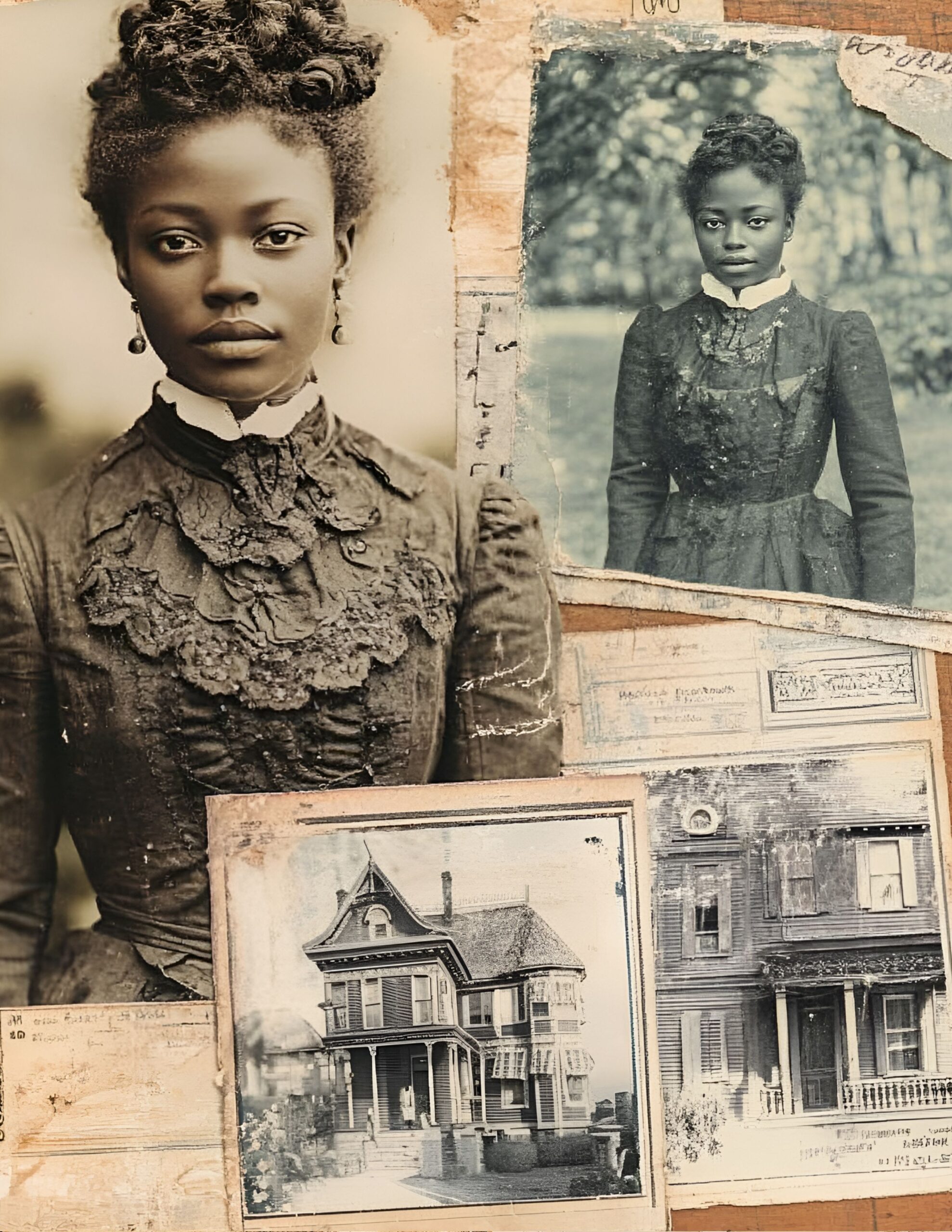

On March 26, 1907, a White police officer named John Cofield visited a home on the north side of Muskogee, Oklahoma — the largest town in what was then called “Indian Territory.” Assisted by volunteer officer Guy Fisher, Cofield had come to evict Carrie Foreman, a 94-year-old Black Cherokee woman.

What happened next became the gossip of a nation still reeling from Reconstruction and the aftermath of relocating Indigenous tribes from the East to the West.

Foreman was a part of a group, she says, “which believed that all property was free.” She told the police she “didn’t have to pay” rent. Her neighbors reported that the home was in high use: Black men and women gathered there at night. When the property manager tried to collect Foreman’s rent, he left empty-handed.

As the officers tried to remove Foreman, other squatters appeared with guns and opened fire. Cofield was shot just above his heart. Fisher was shot in the shoulder. Eyewitnesses alerted federal marshals, already stationed in town, who rushed to the home. A fierce shootout left three squatters dead and three injured. Marshals and police arrested six more, vowing to eliminate Foreman’s group.

This act of tenant unrest blended with racial upheaval sparked nationwide conversation. For a brief moment, newspapers across the country spread word of a “secret society” of “Negro fanatics” called the United Socialists. Police, journalists, and ordinary settlers didn’t know what to make of them. Were they revolutionaries, a religious cult, or a swindling scheme? A scattered historical record suggests that they were an unusual kind of messianic movement, one that drew from the spiritual practices and political contradictions of poor Black people in the American West. In the process, they defiantly challenged the logic of political sovereignty and land ownership that shaped Western expansion. Their ideology consisted of two basic tenets: The group could “seize any property and occupy it,” and “the United States had no authority to interfere.”

The origin story of the United Socialists can be pieced together primarily from newspaper accounts. They were rumored to have chapters across the eastern side of modern-day Oklahoma, but the group was based in the Muscogee (or Creek) Nation’s area of relocation. They were powerful in their own right. Although a White-led socialist movement flourished in the region, the United Socialists “had no direct connection” to any established party.

A Trail of Tears and a Blending of Culture

In the 1830s, the Creek were forcefully relocated from their ancestral homelands in Georgia to parts of Oklahoma along the Trail of Tears. Among the migrants were so-called “African Creeks,” a large contingent of both free and enslaved Black people who’d lived among the tribe for generations. The complex dynamic between these tribal members shifted in 1887 when the federal Dawes Act divided communal reservation land into individual plots. To determine eligibility for these plots, the U.S. government heavily relied on blood quantum, which essentially blocked many racially mixed, adopted or recently-freed African Creeks from becoming landowners.

At the same time, thousands of Southern Black migrants (known as “Exodusters”) were heading west. They were running from the anti-Black terrorism of the post-Civil War southern states. As a result, the Black population of “Indian Territory” nearly doubled between 1890 and 1900. In Creek holdings, these Exodusters formed vibrant Black districts in towns like Wagoner and Muskogee. But Indian Territory’s biracial and adopted Black inhabitants were methodically excluded from legal frameworks for property ownership in the lands ceded to the Five Nations by the United States government. Some settlers, like lawyer and land developer Edward McCabe, hoped to create an all-Black state. His vision was never realized, but between 1865 and 1920, more than 50 all-Black settlements were founded in the lands that became Oklahoma — more than any other region of the U.S.

Enter the United Socialists

Inside this milieu of the search for Native and Black land ownership and sovereignty came the words of a Black preacher named William Wright. Wright arrived in Wagoner, a town about 40 miles east of Tulsa, in the early 1900s. Known by locals as an eccentric, he quickly gained the nickname “The Anarchist.” His teachings combined Christian scripture with folk mysticism and elements of revolutionary socialism. He had a utopian vision of Black resistance, claiming via local newspapers that “either by divine right or by force… the Negroes would shortly drive the Whites from Indian Territory.”

He soon amassed a following of over 200 Black supporters, which included both Southern migrants and Black Indigenous people. He called this group the “Tenth Cavalry,” a possible reference to the all-Black regiment of “Buffalo Soldiers” who served in the U.S. Army after the Civil War. Wright seemed to have a fascination with government authority. He sent numerous letters to the White House, hoping to contact President Teddy Roosevelt. In some accounts, he claimed to receive authority from Roosevelt himself to teach and fundraise freely. A member of the Secret Service visited Wagoner to dissuade Wright’s activity, but he was undeterred.

In 1906, Wright and two of his followers were arrested for resisting law enforcement. They were sent to a federal jail in Muskogee. In the coming days, more of Wright’s followers traveled from neighboring settlements and raised the funds to pay his bail. After his release, Wright moved his base of operations to Muskogee, where he renamed his group the “United Socialists.” His support base increased to around 300, and the group’s practices became more complex.

Part of this new complexity included public rallies, membership fees, and instructing members to occupy vacant homes or to refuse payment of leases. These homes became the group’s meeting places. Signs on the doors warned landlords and police to stay away: “Mind how you step, for your foot might slip and your soul be lost.” By occupying homes and refusing to pay rent, members claimed the right to live wherever they saw fit—disregarding the property laws that governed Muskogee.

At night, Wright would lead members to the outskirts of town where he practiced dowsing — a form of divination used to locate valuable items underground. Using a “divining rod,” he directed them to dig for gold, silver, and buried caches of money. New members paid entrance fees in exchange for spiritual protection, physical protection from law enforcement, and the chance to share in this hidden wealth.

When members were harassed or evicted, they flashed fake detective badges from Cincinnati and insisted they were above the law. But the Muskogee shootout involving Foreman’s home seems to be the only reported record of violent resistance. In the aftermath of Foreman’s eviction, police arrested their remaining leadership. Meanwhile, rank-and-file members continued to preach Wright’s message in nearby towns. Rumors briefly spread that the group’s true leader wasn’t Wright at all, but a 50-year-old White man “with a white flowing beard and tottering steps.” But this was never proven, and Wright was detained for almost a year before going to trial. In 1908, he was convicted of “assault with intent to kill” and sentenced to five years in prison. By 1912, he was pardoned by then-Governor Lee Cruce.

Toward a Greater Understanding

The story of the United Socialists is largely forgotten because members were considered a threat by White settlers, middle- and upper-class Black settlers, and the U.S. government. But the reasons for the group’s existence in the first place were because of the government. After the Civil War, many Black communities saw land redistribution as a necessary part of post-war rebuilding. This was embodied by the temporary order of “forty acres and mule” in 1865 — the product of discussions between Union military leaders and Black ministers in Georgia — which granted 400,000 acres of Southern coastal land to former slaves until President Andrew Johnson overturned the decision. The phrase became a symbol of Reconstruction’s unfulfilled promises and the limitations of state-sanctioned land reform.

Pockets of Black freedmen across the country refused to wait for land to be allotted or protected by government authorities. Instead, they experimented with autonomous communes, worker-run cooperatives, and armed insurrections. These experiments flourished in the lands that became Oklahoma. Wright and his followers were uninterested in using traditional political tactics or in claiming land legally. Rather than founding or joining separatist settlements, they chose to live in and around cities, taking money and housing while awaiting a divinely-ordained mass rebellion.

Seven months after the Foreman shootout, Indian Territory became part of the new state of Oklahoma. Jim Crow and the assimilation of Indigenous cultures became cornerstones of social policy. Black and Indigenous people continued to fight for sovereignty through militant protests, armed uprisings like the Green Corn Rebellion, and building wealth in self-sustaining communities. In turn, White settlers destroyed Black communities in events like the Tulsa Race Massacre and seized Indigenous land through conservatorships and murder. Despite repressive policies and the constant threat of violence, the United Socialists are a powerful example of how Black Oklahomans built a unique tradition of resistance — carrying their desire for self-determination outside and against the law.

Editorial Note: This article first appeared on The Emancipator and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.