How a league of Black housewives changed the Detroit workforce in the 1930s

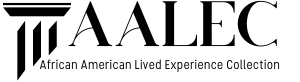

The Detroit Housewives League (DHL), founded in 1930 by Fannie B. Peck, was a pioneering organization that played a crucial role in promoting economic empowerment within Detroit’s African American community

The Detroit Housewives League (DHL), founded in 1930 by Fannie B. Peck, was a pioneering organization that played a crucial role in promoting economic empowerment within Detroit’s African American community during the early 20th century. Its initiatives not only bolstered Black-owned businesses but also challenged discriminatory employment practices, leaving an indelible mark on the city’s socio-economic landscape.

In the aftermath of the 1929 stock market crash, African American communities faced heightened economic challenges, exacerbated by systemic racial discrimination. Recognizing the pressing need for economic self-sufficiency, Fannie B. Peck, inspired by her husband Rev. William Peck’s establishment of the Booker T. Washington Trade Association, convened a meeting of fifty African American housewives in Detroit. This gathering led to the formation of the DHL, with a clear mission: to promote and support Black-owned businesses and to advocate for the employment of African Americans in various enterprises.

The League adopted the compelling slogan, “Don’t buy where you can’t work,” encapsulating their strategy to leverage collective purchasing power to combat discriminatory hiring practices. By encouraging African Americans to patronize businesses that employed Black workers and boycotting those that did not, the DHL sought to create economic opportunities and foster a sense of community solidarity.

A Powerhouse for the Black Working Class

The success of the Detroit chapter inspired the establishment of Housewives’ League chapters in other cities, including Harlem, Baltimore, Chicago, Washington, D.C., Cleveland, and Pittsburgh. By 1933, a national committee was formed, leading to the creation of the National Housewives’ League of America, Inc., with Fannie B. Peck elected as its first president.

In addition, members of the DHL were instrumental in founding business schools and commercial institutes in Detroit, such as the Slade-Gragg Academy of Practical Arts and the Detroit Institute of Commerce. These institutions provided crucial skills to future entrepreneurs and trained workers who went on to secure jobs in Detroit’s expanding Black enterprises. The DHL also organized Junior Units for children and educational units for older youth. These programs aimed to instill an appreciation for Black-owned businesses and provided training for careers in business, thereby ensuring the sustainability of economic progress within the community.

The League’s campaigns pressured white-owned businesses to hire African Americans, effectively using economic influence to combat employment discrimination. Their efforts contributed to a more inclusive hiring climate in Detroit, providing increased job opportunities for African Americans during a time of widespread racial discrimination.

During the war, the DHL played an instrumental role in consumer education, focusing on conservation, price watching, and rationing. They actively participated in the Office of Price Administration panels, ensuring fair pricing and preventing exploitation in their communities.

The Detroit Housewives League’s emphasis on economic self-sufficiency and community solidarity set a precedent for future civil rights activism. By mobilizing African American women and leveraging collective economic power, the DHL not only supported Black-owned businesses but also fostered a sense of empowerment and agency within the community. Their strategies and accomplishments continue to serve as a testament to the impact of organized, grassroots economic activism in the pursuit of social justice.